Monetary policies, in practice as in theory, necessarily adapt to changes in the way the economy is regulated and, by construction, to successive changes in inflation regimes.

The appearance of high inflation during the 1970s led to a change in the use and theory of monetary policy at the end of the decade and in the first half of the 1980s. The literature of the time endorsed the idea that the monetary weapon must be dedicated to the fight against inflation, creating a consensus on the fact that there could be no effective arbitrage between the fight against unemployment and the fight against inflation. In the medium-to long-term, accepting more inflation to strengthen growth only caused an increase in structural inflation, without an increase in the pace of growth. From 1979, Volcker heavily restricted the expansion of the monetary base (the quantity of central bank money), which raised interest rates to record highs and, in doing so, caused a strong recession.

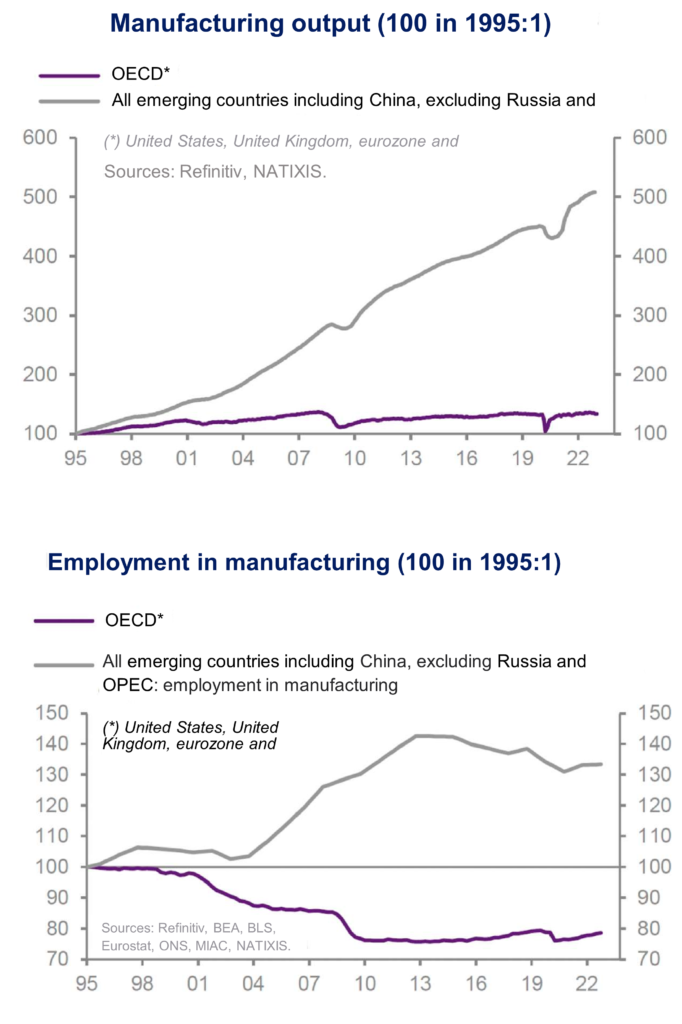

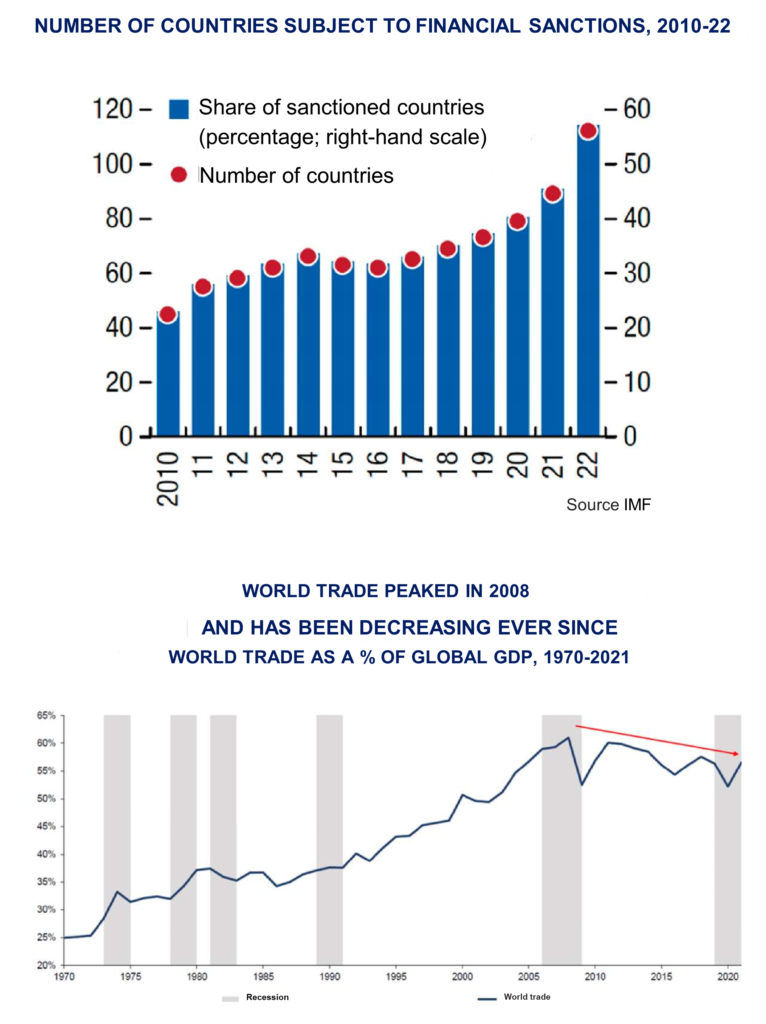

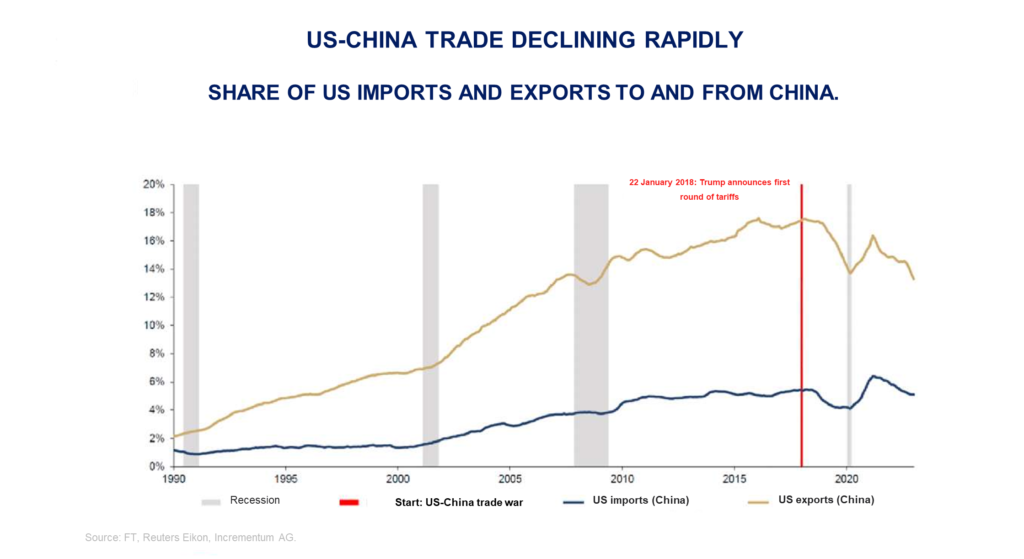

The resulting cyclical drop in inflation gradually led to a structural regime of low inflation. Monetary policy was not the only reason here, or even the major reason. The 1980s were in fact, on the one hand, a time of financial liberalisation (deregulation and globalisation) and, on the other hand, in the real sphere, the very beginning of globalisation, which was greatly accentuated during the following two decades.

The effects of technological developments

Financial globalisation has put increased pressure on long-term interest rates in countries experiencing comparatively high inflation. And globalisation has led to the emergence of a competitive workforce cheaper than that of developed countries, implying necessary wage moderation in advanced countries. But also symmetrically a massive exit

from poverty in emerging countries.

The 1990s and 2000s also brought a new technological revolution. The digital and robotics revolution, while statistically it has not shown clear evidence of an increase in productivity gains, has nevertheless slowed the growth of wages, in particular for the least qualified workforce, via the possibilities of substituting work by automation which it facilitates for

certain categories of tasks.

Thus, once again, as at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, low inflation was established for the long term, made possible by the return of the globalisation of the capital and commodity markets as well as investments and by the development of a new technological revolution. As a result, the 1990s and 2000s meant that monetary policy could be used not only to combat inflation but also to further promote regular growth at a good level.

From money supply to interest rates

Hence a new evolution of economic theory, in support of this new practice. On the one hand, it justified abandoning the money supply as an instrument of monetary regulation, to highlight the essential role of interest rate rules, i.e. the setting of key (short term) interest rates by central banks. In practice as in theory, exit LM from theoretical and econometric models (see Jean-Paul Pollin, Une macro-économie sans LM, Revue d’économie politique, March 2003). And on the other hand, the new theory of monetary policy argued that there were optimal interest rate rules that simultaneously kept inflation at the desired target level (2% increasingly became the benchmark) and ensure regular and balanced growth. This gave central banks the new ability to institute a period of great moderation, during which real cycles were greatly attenuated and inflation was almost, if not completely, under control.

The reappearance of financial cycles

However, parallel to this apparent great temperance, another phenomenon has gradually gained momentum and has not been taken into consideration by most theoreticians as well as practitioners of monetary policy. This is the reappearance of financial cycles, interacting with real cycles but with a significant degree of autonomy due to their own dynamics. These financial cycles had, however, been concomitant, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, with financial globalisation and globalisation. But their ability to cause severe financial instability, with profound economic consequences, was largely ignored until the new major financial crisis of 2007-2009. In the theory forged in the 1990s and prevailing until the great crisis, financial stability was in fact considered to be a given as long as regular growth and stable inflation were both established.

However, without much attention and therefore without much monitoring, financial cycles have once again developed, longer than real cycles, made up of several phases.

With long enough real growth, a phase of rising debt rates (in the private and/or public sector depending on the period) and the development of bubbles in property assets (mainly stocks and real estate) gradually begins. This leads to a phase of euphoria where we end up collectively thinking that growth will continue forever and that the prices of heritage assets will rise constantly, giving valid reasons for this each time. The

financial cycle, in its paroxysmal phase, ends with a violent reversal, due to a sudden change of opinion, a rupture of previous conventions which until then legitimised the level of debt ratios, leverage, multiples of valuation, etc., although historically very high.

Ensure multidimensional stability

These reversals of phases are partly due to the fact that it becomes more and more difficult to rationally justify these phenomena, but also because euphoric anticipations always end up being disappointed sooner or later. Finally, let us note the role of chance in these sudden changes of opinion, in these mass stampedes. De facto, certain events, however significant, do not cause any rupture, while others, sometimes seemingly more insignificant, end up doing so. Thus begins the final, catastrophic phase of the cycle, with bursting of bubbles, a sudden rise in the insolvency of a number of economic agents and recession, in a context where borrowers then seek to significantly lower their leverage and where lenders can rationally, out of fear of the future, limit their credits. All of which drive each other into a vicious cycle and contain a high risk of depression and deflation.

Thus, in such a model of regulating the economy, the stability of prices at a low level and the regularity of growth do not automatically lead to financial stability. On the contrary, the low inflation policy that this mode of regulation generates leads to structurally low interest rates, which in turn encourage increasing debt and bubbles. Monetary regulation must

therefore in reality, during these periods, ensure multidimensional stability. It must strive to promote monetary stability (inflation as its objective), a regular and an adequate level of growth (effective growth as its potential), but also financial stability (fighting against an unreasonable rise in public and/or private debt rates and against destabilising speculative dynamics).

Financial deregulation and globalisation, as the long history has taught us, thus facilitate financial instability, itself linked to the intrinsic pro-cyclicality of finance. Even if, moreover, they also produce favorable effects of which is not the issue here. In such a context, it is therefore not a question of wanting to re-fragment the financial markets, but, through appropriate regulations and ad hoc policies, of knowing how to limit this pro-cyclicality as much as possible beforehand and of limiting the potentially catastrophic effects when they occur.

Fundamental uncertainty

This intrinsic pro-cyclicality and instability of finance are thus due to this endogenous uncertainty, qualified as fundamental or radical uncertainty, different from risk situations which allow a probabilistic calculation. They are also due to the simultaneous existence of an information asymmetry between the co-contracting economic agents − here for example between the lender and the borrower − which does not allow prices (or interest rates) to always play their role of balancing supply and demand. But they are also due to the presence of cognitive biases which reveal the insufficient realism of pure rationality defined and assumed by canonical models. These concepts, which make it possible to develop a theory closer to reality, more faithful to the world as it is, do not, however, call into question individual rationality. On the one hand, they provide the means to take into account a rationality that is itself more realistic, that is to say a limited rationality (the cognitive power of individuals is not infinite) and a contextual rationality (it depends on the elements of knowledge at our disposal). On the other hand, they make it possible to analyse why the sum of individual rationalities does not systematically give rise to collective rationality. In other words, why the sum of the rationalities of each, in certain circumstances, comes out of a “corridor” in which the spontaneous way actors play leads to a return to balance, but in the opposite way builds cumulative imbalances which induce a generalised vulnerability of the system (See in particular Leijonhufvud, Nature of an Economy, CEPR, February 2011).

Equipped with the prevailing theories at the time, the monetary authorities were thus unable, before the huge financial and economic crisis of 2007-2009 violently erupted, to take into account these financial cycles which see debt and bubbles expand. However, from 1987 (equities), then during 1990, 1991 and the following years (real estate), in 1997 and 1998 (sudden stop crises in emerging countries), in 2000 (equities) and of course in 2007-2009 (debt and real estate), systemic crises have reappeared, consisting of the bursting of successive speculative bubbles and increasingly pronounced credit and overindebtedness crises.

On the other hand, the return of systemic financial crises has provoked, at the international level, a salutary reaction from central banks and regulators. First of all they were able to avoid catastrophic events in these crises and to avoid the return of long periods of depression which historically follow such situations (Reinhart and Rogoff, This time it’s different, eight centuries of financial madness, Pearson, 2013 ), as was the case during the crisis of 1929. And this, thanks to curative actions, with the reaffirmed role of the central bank as lender of last resort, and preventive measures, by limiting the risks taken by banks through imposing an increase, notably in equity capital in proportion to the risks taken, to absorb possible significant losses. Then, after the great financial crisis of 2007-2009, by additionally putting in place, among other things, so-called macro-prudential regulations, in order to limit the pro-cyclicality of credit and financial markets, notably through tightening or easing counter-cyclical prudential rules, and finally by imposing liquidity ratios on banks.

Insufficiently low long-term rates

As a curative action, in order to avoid the devastating effects of systemic crises once they are triggered, including long depression and deflation, central banks have, rightly, lowered their key rates towards zero, or for some even below zero (including the ECB). But they had to face the constraint of the minimum rate being zero (“zero lower bound”), or even the constraint of the minimum rate being a little below zero (“effective lower bound”). These rates have in fact proven to be insufficiently low to avoid the risk of deflation and to bring long-term rates down as much as needed. As a result, they became innovative by launching a policy considered unconventional, that of Quantitative Easing (QE), which consists of purchasing securities directly on the markets, of thus taking virtual control of long rates and risk premiums, particularly bond premiums. Note, however, that the central bank of Japan had implemented such a policy much earlier to deal with the consequences of the violent burst in 1990 and the following years (“the lost decade”) with their major bubbles on the stock market as well as on that of real estate, leading to lasting economic stagnation and deflation.

Central banks dramatically increased their balance sheets in doing so, causing a considerable increase in the quantity of central bank money. Hence the name quantitative easing. These policies thus prevented any self-destructive speculative hype. And, after the peak of the crisis, they facilitated the debt relief of the many players requiring it, by positioning long-term market interest rates below the nominal growth rate.

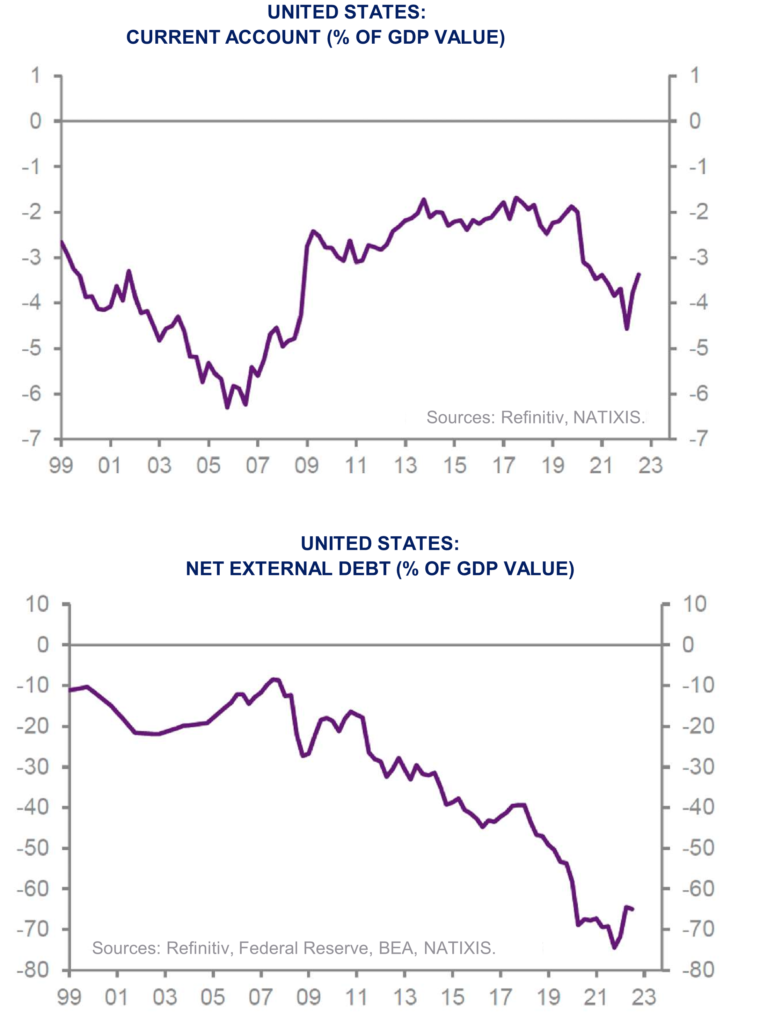

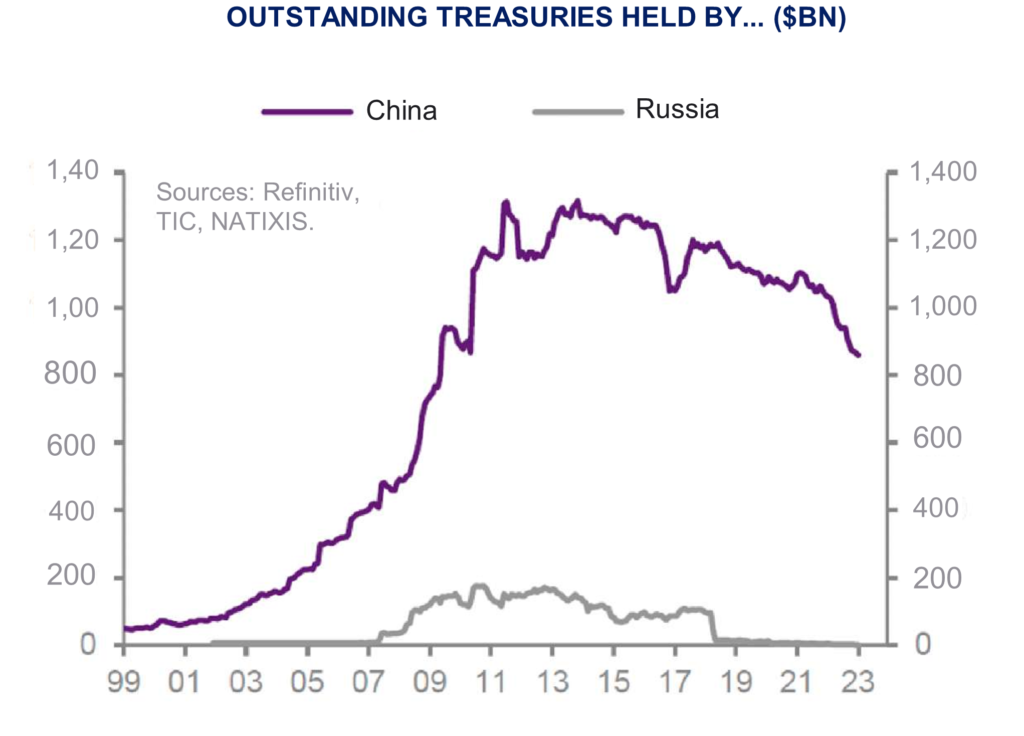

But, when economic growth became satisfactory again and loan output returned to a pre-crisis pace, the central banks did not end their QE policy (or tried to do so and then quickly abandoned it, as with the Fed). We can analyse the reasons why. In any event, this has caused a problematic asymmetry in the conduct of monetary policy, since, during a severe shock, they have rightly put in place unconventional policies which they have not removed, even carefully, when normal growth returns. By thus maintaining rates that are too low in relation to the growth rate for too long, monetary policies have gradually facilitated, in many countries, both advanced and emerging, a very high valuation of the stock market and an even more visible real estate market bubble, as well as a sharp rise in debt relative to GDP.

Structural inflation below 2%

What were the explicit or unspoken reasons that pushed central banks

towards this asymmetry? The answer frequently put forward is the

persistence of an inflation rate that is too low compared to the inflation target of 2%. And the existence of an extremely low natural interest rate, which can be an indicator for analysing the accommodative or restrictive nature of monetary policy. This rate, unobservable, but the result of a model, is defined as that which ensures that the effective growth rate is

equal to the potential growth rate, with inflation stable and equal to the objective level. However, without going further into the debate (Cf How to avoid the debt trap after the pandemic? Olivier Klein, Revue d’économique financier, May 2021), let it be noted that the underlying model is open to criticism from different points of view and that the inflation policy induced by globalisation and the digital revolution very likely generated structural inflation below the 2% objective. Central banks have fought in vain, as the facts show, against inflation, probably wrongly considered too low, by keeping interest rates too low for too long. Let us add that a protracted policy of very low rates ends up lowering the interest rate itself in the long term (Cf What anchors the natural rate of interest, Claudio Borio, BIS working papers, March 2019).

The tacit reasons were probably, in the United States, to seek to push growth on a long term basis above its potential to increase the

employment rate and, in the euro zone, to protect the integrity of the monetary zone, which could have suffered from a rise in interest rates, while the insufficient convergence of the structures and economic conditions of the different member countries was clear. Let us add that the fear of a rise in interest rates creating a strong impact on the valuations of heritage assets and the insolvency of many players, including public ones − even more so when inflation was not an issue − had to play a role in maintaining these unconventional policies.

The turning point of 2022

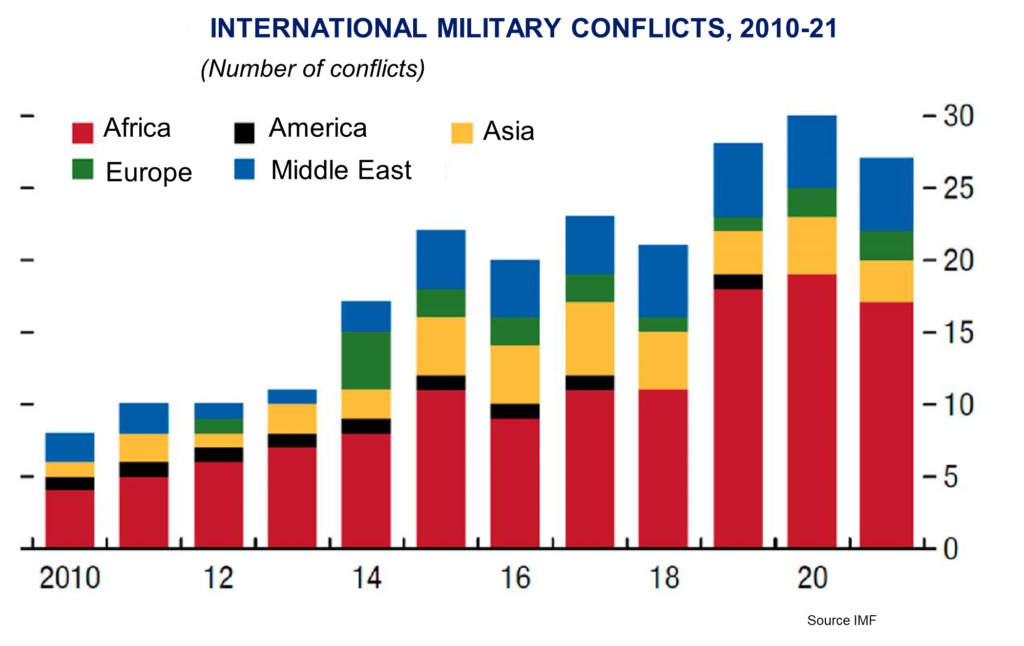

However, be that as it may, inflation made its comeback after the end of the lockdowns, generated by restricted supply and boosted demand, further fuelled by the impact of the war in Ukraine on energy and agricultural products prices. This brings us to the turning point for monetary policies in 2022 and the ridge path they must now follow. The sudden dramatic rise of inflation necessarily led central banks to sharply increase their key rates. On the one hand because inflation is very unfavourable for businesses and households which cannot easily match the price increases in their own prices or salaries. On the other hand, because high and unstable inflation results in the loss of the benchmarks necessary for an orderly, confident, and therefore uncontested, setting of prices and wages, essential to an efficient economy, and can lead to an inflationary regime of generalised indexation, leading to uncontrolled inflation. Additionally, it was necessary to finally emerge from a period where interest rates were too low for too long, with the consequences described above. All these reasons explain why after having hesitated over the transitory nature or not of inflation, the central banks raised rapidly and strongly their key rates. And at the same time the beginning of quantitative tightening which they proceeded.

But we must also highlight the unique situation that central banks are faced with today and which requires them to proceed very cautiously from now on and to move forward, implementing monetary policy in small steps, paying particular attention to the careful study of data between each decision, in order to identify the effect of their own policy on inflation, real growth, and financial stability.

Underlying inflation has not been defeated and requires higher rates or at least being maintained at current levels over the long term. But, at the same time, a rise that is too rapid or too strong can materialise the accumulated financial vulnerabilities generated by rates that have been too low for too long, on the liabilities side of balance sheets (too much debt) or on the assets side (highly or overly valued assets) of numerous private and public players. Interest rates at the current level, or even higher, have and will tend to put a strain on the financial robustness of many players and the continuation of a very high valuation of heritage assets. Moreover, real estate, in many countries, has started to show significant signs of weakness, even warning signs of a pronounced reversal of the cycle. The central banks have therefore begun a use of monetary policy which will constantly scrutinise the state of overall financial stability and the leading indicators of the economy. They will therefore be cautious. Without losing their essential credibility in their fight against inflation. Central banks must not in fact be dominated by either budgetary policies or financial markets.

Monetary policy cannot do everything

Finally, let us emphasise that we very probably expected too much from monetary policy alone. It can’t do everything. It is crucial that fiscal policy is shaped in a way that is compatible with the phase in which the economy finds itself. Until then, there is no need to support overall demand since the end of the lockdowns, even if it has been desirable to protect the weakest populations in the face of the very sharp increase in food and energy prices. It is no less crucial that the essential structural reforms are carried out. As inflation results in this case from the impact of supply and demand for goods and services, but also for work, it is particularly important to develop production and sustainably increase the number of people available in the the job market. Through structural policies, it is therefore essential to raise the level of potential growth in order to best avoid the detrimental effects of excessively high debt ratios, especially when interest rates return to normal.

Is it still possible to value financial assets objectively?

The propensity for financial instability is due to the fragility of conventions (common opinions), which are not based on the objective foundations of a probabilistic forecast of future financial asset prices. As the various states of the future world are recurrently difficult to predict, the possibility of a rational and objective (not self-referential) valuation of assets at any time, always leading to fundamental or equilibrium prices, is in fact an assumption that can regularly prove to be heroic.

The same applies to the assessment of the solvency of economic agents, which is essentially endogenous to the system, i.e. again self-referential. Solvency stems from the fact that everyone believes that the company or government in question will subsequently be able to refinance its debt under normal conditions. This obviously depends on future trends in economic data and the borrower’s specific financial ratios. But also, by construction, on what the average opinion thinks today will be tomorrow’s average opinion on these subjects. The average expectation of what will be acceptable to everyone in the future is crucial in determining the solvency of an economic agent. This is the hallmark of a self-referential phenomenon that is endogenous to the system.