My first thought is that it is a rare day when, on opening the newspapers, we do not see articles about banks, predicting that we are the new steel industry. I even recently read we are destined to turn into Kodak, which as everyone knows failed to see the technological revolution, fatally as it turned out. So working in banking is very encouraging at the moment. Many employees in our banks are accordingly in a state of uncertainty, and some are just plain seriously worried about the future of jobs in banking.

I am going to try to deal with the topic by revisiting what the President said to introduce the subject. Bill Gates in fact said that “banking is necessary but banks are not”, which is entirely in keeping with the Kodak episode.

I would nonetheless like to remind everyone that he said it in 1994. I feel bound to point out that banks are still here. We will try to demonstrate, rather than just believe, that retail banks will still be here for many years.

Obviously, though, the question arises, and rightly so, because digitisation and globalisation are, in my view, two fundamental revolutions we are experiencing. These are really the two major factors changing the lives of companies and banks in particular. Digital is a technological revolution, but also as a consequence, a revolution in customer behaviour, including in their dealings with banks. Accordingly, the number of customers in our branches is seen to be decreasing considerably and continuously, which leads some to think that as people no longer come to branches, we no longer need branches and no longer need customer advisors. Therefore, the only option, the best option, is said to be a defensive stance. Cut our cloth as much as possible.

I think there are fundamental questions that need to be addressed, which cannot be swept under the carpet, but at the same time, I think that banks, and here we are talking more about retail banks, have some valuable trump cards they can play. The point is, however, not to stick with the usual way of doing things, changing nothing. That would be fatal. On the other hand, however, I think retail banks have the potential to “take the high road” out of the situation, a road I am going to try to highlight.

To do this, we need to think a little more deeply and return to the very essence of the banking relationship and of the banking profession, in retail banking.

In actual fact, there are two areas where the bank operates, not juxtaposed but coordinated with each other, while also being different from each other. Historically in banking, there are banks I would call transaction banks, i.e. a bank for everyday banking, making payments, withdrawals and deposits. The structure of this bank means it can very comfortably digitise completely. With ATMs and smartphones, which can increasingly be used for such transactions, humans can quite simply be dispensed with.

As a result, a number of banks may appear, neo-banks, online banks, almost all of them low-cost banks, dedicated to this transaction handling role, in a cheaper and sometimes more convenient way than traditional banks. Although traditional banks have invested sufficiently lately to catch up. The reason is these new banks are starting from scratch and setting up as online, low-cost banks with very few employees. They often build a new computer system and this is infinitely easier than overhauling all your IT when it has been built layer on layer for years, as it has in all companies and especially in all banks. Consequently, customers find services more practical to use, and the cost this kind of bank can charge is inherently lower. You have to look closely though, because most of the time, when low-cost banks advertise that they are free of charge, it’s just advertising flannel.

But can these newcomers, based on new technology, cause us to disappear?

The first response from our banks is that we have considerable investment capacity and we have very valuable staff and so on. We obviously have to fight against the effects of unwieldy information systems, but nevertheless we can, by investing heavily in digital, definitely manage to digitise processes, to make customers’ relationships with their bank infinitely more practical, to ensure that we are among the best. We can at least be just as practical as the newcomers.

Is that enough? I believe that some major banks consider this to be their main line of defence, reducing costs by cutting the number of branches and customer advisers. So, heavy investment in IT is needed, absolutely necessary to develop digital, to develop “self-care”, and ultimately reduce costs as much as possible to try to move towards an intermediate model between traditional high street banking and online banking.

It is my modest belief that this strategy must obviously be considered, but it includes a high proportion of risk. It is a strategy that could lead to regular attrition of the entire system, because often when branches are closed and advisors sacked, customers are lost. And if every time we lose customers, we lose revenue, we are going to be forced to make further cuts and therefore fresh attrition results. The process is endless.

Of course, we must have optimum cost management but, ultimately, all businesses always need that. We must, on the other hand, guard against falling into the circle of attrition.

So what then is the answer? I said firstly invest heavily in digital and make ourselves at least as practical as online banks. I can tell you that most banks in France today have become or are becoming as practical as online banks. But the answer is also to take due account of the fact that online banks themselves only meet some of their customers’ range of needs.

Online banks focus on transactions. They cannot offer advice since they are not advisors. While they are gradually gaining customer advisors, they then need to be accommodated somewhere, be paid, and they need to be trained. This means their costs would rise significantly, and they would therefore no longer be low cost. Eventually, we could then see business models converge. But meanwhile, they do not have customer advisors.

What is the other part of the banking model covered by conventional banking in France? What I call relational banking. Relational banking means banking advice, banking for all of life’s plans. The bank incorporates both models and coordinates one with the other, as I was saying. In relational banking, advisors support their customers’ plans for the future and businesses’ plans. These might be major personal plans, buying or extending a home, starting work, preparing for retirement, preparing a will, preparing for children’s education. They might be minor plans, a luxury trip, the purchase of a car, etc. All this is in actual fact dealt with over a long timeframe. In the way that the transactional bank operates in a short timeframe, so the relational bank operates in long timeframes, because future plans require preparation before they are then acted upon, and they tend to happen gradually. And which are the bank products that match that description precisely? Loans, savings and insurance. These are all products that operate gradually, over a period time. So one has to save up in advance before preparing for some future plan, or save after obtaining the loan that was spent on one’s plans. French customers generally do both at once. Insurance naturally protects their property and their family. All these products constitute a comprehensive range of banking services, suited to all plans customers might have, supporting those customers and finding solutions for them and their families.

So, with supermarkets, the timeframe is immediate, not a long period. When you go to a supermarket, or any type of shop, the act of purchase is in the here and now. If you are not happy with a product, you can change brands the next day. If you are not happy with a shop because it doesn’t stock the brands you like, you can change shops the next day. There is no long-term relationship. This is also why there are fewer and fewer sales assistants in shops. They have been replaced by rows of shelves and self service. In contrast, in banking for customers’ plans, we are looking at the long run. As a result, when major retailers thought about including banking services, they stopped at consumer credit, which is the exact link between short and long term. They have stopped at payment methods, where appropriate, to expand their loyalty cards, but have not moved on to the rest. Some supermarkets have tried, but they never quite managed to sell shrink-wrapped savings accounts. For the same reasons, I think relational banking does have a future, because it meets an interpersonal need for support and guidance over the long term.

Let us delve a little deeper. Is this true is all countries? Not really. In some European countries, and more so in the English-speaking world, banking has been fragmented for a long time. Perhaps indeed banking has never been unified. In the United States, it is not uncommon for someone to have one bank for payments, consumer loans with specialist lenders, a property loan from another specialist provider, and investments placed with brokers. It is actually the usual state of affairs. In countries where banks are predominantly for transactional purposes, the strategy of severe cost cutting is inevitably followed. But France is a country where relational banking is a strong factor.

Second point. Online banks which have existed for a few years, although they are still young, are not profitable. Not one in France makes any money. Why is that? Because it is very difficult, even when costs are pared to the bone, to give customers more and more, and retain them. And that is because there are no customer advisors. Furthermore, they do not have the presence on the high street to attract new customers that we have. Obviously not, a low-cost, online bank by definition does not have a high street presence. Therefore to attract customers, they are forced to hand out the freebies you all know; €80 for a new customer and a bank card, typically for life, albeit under certain conditions. This costs online banks a great deal. Moreover, at least €50m of advertising per year is needed to sustain the brand and be in a position to acquire new customers. All in all, customer acquisition is extremely costly.

However, once the necessary investment has been made to increase the practical usefulness of banks and make them comparable with online banks in this respect, is the lion’s share of the work complete? Is differentiation by having customer advisors enough? Is the relational aspect well perceived by customers and do banks keep their word in this area? Because if the relational aspect is pointless, why then do customers not go to the cheaper online banks? Can we assume that, in the field of relational banking, traditional banks are fully up to speed? Of course not. We still need to move forward and improve upon our own business model, i.e. leveraging our differentiation. And it is by improving our differentiation, promoting it more, making it even better, more visible, more tangible, that this differentiation will probably enable us to survive and even continue to grow. In fact, by making our relational service promise both credible and demonstrable.

For example, regardless of the bank, it is possible from time to time to have advisors who know less than their customers. It is also possible to have advisors who change a great deal, every year or year and a half. As a result, long-term relationships are not established, and good customer knowledge fails to take root. I could obviously add many more items. For example, perhaps from time to time there is a lack of responsiveness in banks, service levels that are not always pushed to their maximum, and so on.

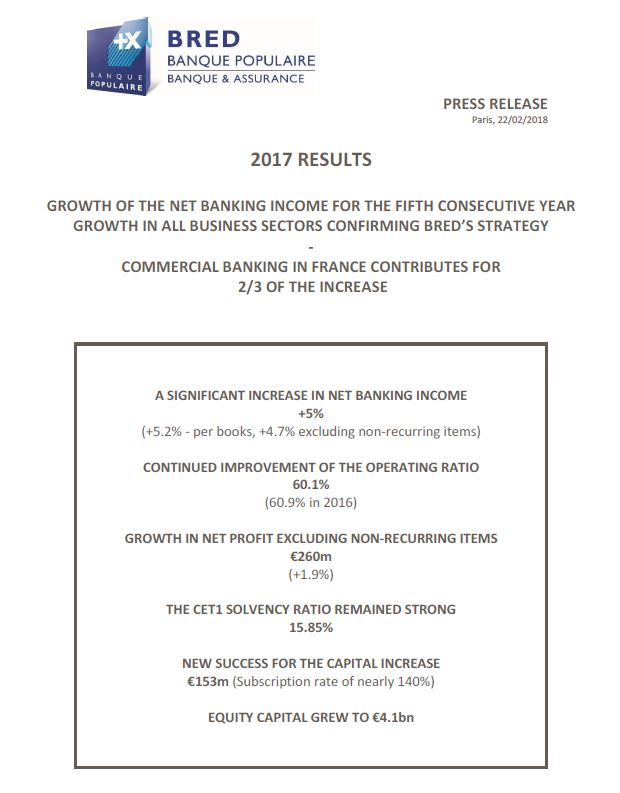

It is therefore essential for our banks, and this is what we have been doing unassumingly at BRED for the last five years, to improve this model, to drive it to its best level. One example is that our customer advisors stay in the job for three to five years with the same customers. Another example is ensuring that customers are segmented properly, on the basis of the greater or lesser complexity of their requirements, in order to place them with advisors with the skills to match. Or for example by substantially increasing the amount of training taken each year.

Incidentally, as the world goes digital and turns to robots, I am convinced that the only way to defend work in developed societies like ours is to increase the added value delivered. This is the knowledge society. It is the innovation society. If we seek to lower costs in the fight against cheaper labour in emerging countries or against imminent robots, we have already lost. It is, of course, possible to have maximum efficiency and optimum costs. These are the basic rules of business, as we have reiterated. But we must also bank on the knowledge society (pun intended). To use BRED as an example, in the last five years we have increased the training budget by 40% and now have a training budget equal to approximately 6% of the wage bill, while in France, as you know, the legal minimum is 1%. We are therefore trying to “take the high road”.

It also means changing sales methods. Meaning we don’t sell the product as the product, we analyse a customer’s requirements, which changes everything. We then look at how to offer solutions appropriate to individual circumstances, using the range of products and services we have. Our role is not to promote a product and push it onto all customers.

We obviously make use of digital there too. Consequently, we don’t only use digital for processes and we don’t only use digital to make life easier for our customers through the quality and utility of our smartphone apps, etc. We also use digital for what is known as “big data” and for processing customer data, and thus give as much information as we can to our advisors as input to best prepare for customer appointments, to deliver the best advice and the highest possible added value.

So to “take the high road” and avoid “Uberisation”, a great deal of investment is needed, consistently and following an appropriate strategy, in both digital and human capital.

Further, the number of customer appointments is in actual fact not falling, although customers no longer visit branches as much. The number is increasing, but these appointments can easily take place over the phone, or using online chat, email, etc. They are real appointments that take some time, appointments to analyse requirements and put solutions in place. Digital tech makes for better preparation for appointments, and enables us to sell products remotely when customers do not wish to travel. But always with an appropriate advisor.

It is therefore vital to put our promise of relational banking into practice and to make sure this is seen by customers to be the case, so they have no desire to leave us.

This seems to me to be the key to success. Being at least as good as online banks at the transaction side of our work. And affirming and enhancing our winning differentiation through the excellence of our relational banking model, as an advisor bank offering customers added value, which online banks, by virtue of their structure, are unable to do.

Ensure that the human factor is ever-present, essentially, because human decisions are decisions taken by both the head and the heart. That is how the decision-making process works. Rationality alone is not enough. The right decision is still something “felt”, so cognitive science teaches us. That must entail human contact, which is therefore crucial. This is and will be our winning differentiating factor: an overall model built on close relationships, augmented by technology.

THE CHAIR:

Thank you Monsieur Klein. Now it is time for questions. I will ask the first one.

What is the banks’ attitude towards crowdfunding? Crowdfunding platforms are currently springing up. What do you think of them, what is your response?

Olivier Klein

I have a slightly iconoclastic point of view on this subject.

Crowdfunding for borrowing must be distinguished from crowdfunding for private equity. For private equity, I’m in favour, because people will place a small amount of money with platforms that will invest in small business with significant growth potential. If that money is lost, too bad. If the capital grows, then great. It is just private equity through the intermediary of a platform.

For borrowing, I’m much less in favour. That does not mean it will not develop to an extent, but it will probably stay fairly minor. I absolutely do not believe it is a route to serious disintermediation of banks. The economic and social utility of a bank lies in the fact it takes the risk in place of its borrower and lender customers. What are these risks? First of all, credit risk, naturally. If you deposit money with the bank, you do not take the credit risk that the bank takes. Unless the bank goes under. In France, that is not something we often see. The cost of credit risk has no kind of consequence on the savings you have deposited. When you lend money on a crowdfunding platform, naturally you are subject to all the credit risks taken by the platform, and you shoulder that risk euro for euro. Meanwhile, the bank alone bears this risk in its own profit and loss account. A crowdfunding platform has just gone bust in the United States. The second and third kind of risk taken by the bank are connected to the fact that the bank, by creating credit and borrowing, generally borrows short term from customers (deposits) and lends long term (credit facilities). There are therefore two risks the bank takes on behalf of either borrowers or savers, and these are interest rate risk and liquidity risk. Banks regularly absorb these risks in their profit and loss accounts, and do not pass them on to customers. Moreover, banks are trained in managing these risks and are also regulated to manage them prudently. On crowdfunding platforms, this is absolutely not the case. Neither does it apply to investment funds, which increasingly undertake non-regulated banking, shadow banking.

Such risk is completely absorbed by investors, or even borrowers.

Question

Who issues bitcoin, who manages bitcoin and blockchain? How do we get access to information?

Olivier Klein

In my bank, we get questions from customers asking what we think of bitcoin and other crypto-currencies. Crypto-currencies are not true currencies in the sense they keep none of the liquidity value invested in these “currencies”, as their price can rise or fall very sharply. These “currencies” have no stability, and are not even nominally anchored. There is no lender of last resort, there is no central bank and, structurally, given what I have just said, there is no stable relationship between currencies. They are private currencies being issued, and that is how I answer your question. They are issued by private concerns who decide to launch a crypto-currency. Private concerns who launch these create a new “currency” and are entitled to take a small percentage of the amount they create themselves. I find that extraordinary.

It should be recalled that in the 19th century, central banks started to be established because private currencies were leading to major financial crises, with unpredictable swings in value; the whole thing collapsed regularly with major economic crises the result. Are current crypto-currencies founded on credit? No, there is no lending. Are they founded on the value of a precious metal? No. They are purely speculative and the whole scheme is hugely similar to tulip bulbs in Holland in the 17th century which caused a major speculative crisis.

Question

Don’t you think that in the banking industry, you tend to compare traditional banking with online banking, but rather than considering online banking as a competitor would it not be worth considering it as an additional product that you could offer those of your customers looking for another kind of customer experience and another form of relationship with their bank?

Olivier Klein

A very good question, and there are banks that have built online banks internally, and at BRED we have one called “BRED Espace”. So I really am not against online banks.

BRED’s online bank is not a low-cost online bank, and nor are those of other banks in BPCE Group. It is a bank that does everything online for people who do not want or really cannot have any kind of relationship with a branch, because they don’t have the time or because they are abroad or for a thousand other good reasons. It is also intended for students who so wish. But all these customers have a qualified advisor. We also encourage a close relationship, even if no branch is involved.

It is indeed a smart move to include online banks for some market segments. If it results in sustained losses, it is of no interest. But if models are found that can generate profits over marginal cost, naturally it could be of interest.

Let us return to the topic of blockchain. Crypto-currencies work using blockchain, but blockchain is a technology used for many other things. It is a technology that is, as you know, highly decentralised. Digital tech goes very well with decentralisation. It even facilitates it. These are therefore what are called miners, companies that develop computer data processing capabilities, storing data by multiplying checks against each other and ultimately certifying the genuineness of something. It could be a certificate, title deed, etc. So, it could be used in some African country to replace a non-existent land registry; or between banks to replace the securities custodian system on behalf of customers, etc. At BRED, we have even developed the ability to use blockchain to check customer identities, especially at the start of the relationship, because banks are now under a regulatory obligation to “know their customers” and confirm their identities. We have therefore developed a service that makes it possible to check numerous points within a few seconds, often using blockchain, to certify the identity of future customers.

So blockchain really cannot be reduced to crypto-currencies alone. The only problem with blockchain is that this way of doing things uses vast amounts of energy and ecologically speaking is probably a disaster. But technologically speaking, it is of great interest.