Conventional and unconventional monetary policies play an essential role during serious crises. They push both short and long interest rates to very low levels, below the growth rate. These very low rates have a direct, favourable impact on demand and an indirect impact by increasing the value of capital assets (notably, real estate and equities). The policies also facilitate deleveraging by making it easier to repay debt. Even spreads are pushed down to ensure that they won’t trigger a catastrophic bankruptcy chain reaction via a brutal increase in insolvency.

However, when these monetary policies are in place for too long, they can become a serious source of danger and a significant risk to financial stability. It is very important, and even indispensable, for central banks to adopt these types of policies in certain situations, from major financial crisis to the deep recession resulting from the handling of the economic consequences of the pandemic. However, they can lead to a problematic asymmetry when growth returns with a significant increase in credit and central banks fail to reverse their policies, do so incompletely, increase their interest rates by too little or fail to reverse their quantitative easing policies, or do so incompletely.

Growth in the eurozone recovered satisfactorily by 2017 and credit was again being issued at a high pace. However, the ECB’s policy remained unchanged. The reason given was that inflation was still too low, that is, the target inflation rate had not yet been reached. In the eyes of the central bank, this justified maintaining an ultra-accommodative monetary policy. However, could monetary policy cause inflation to increase? Wasn’t inflation structurally, and not cyclically, very low? In this type of situation, it became dangerous to continue the policy for too long because it maintained interest rates below the growth rate: interest rates were kept too low for too long. This caused the return of a financial cycle with debt rising faster than economic growth and the return of capital asset bubbles, notably in real-estate and equities. It was accompanied by a loop effect, as are all financial cycles, because, in this case, debt was also used to buy capital assets, which fed the bubbles and facilitated the accumulation of more debt.

Whenever interest rates are kept too low for too long, the financial vulnerability of the overall economy increases with significantly more serious risks on balance sheets, in the assets of some groups and the liabilities of others.

1. In the assets of financial investors and savers. In this type of interest rate situation, these players look for returns at any cost, since interest rates are too low. They take on more and more risk in order to obtain it. Risk premiums are thus compressed in a way that is completely abnormal and dangerous: when the bubbles burst, spreads simply cannot cover the cost of proven risk. The assets of savers and of the financial investors who work for them (pension funds, insurers, investment funds, etc.), are thus vulnerable. Starting before the pandemic, this led to a historical drop in yields on investments in infrastructure, to historically low credit spreads on high-yield and investment-grade debt, to very high valuations for listed and private equity companies, to investment funds holding increasingly illiquid assets and/or with very long maturities while ensuring the daily liquidity of those same funds, etc.

2. In borrowers’ liabilities. Borrowers tend to take on too much debt in this type of environment, since the cost of money is low compared to the growth rate, resulting in excessively high leverage. This includes, among other things, share buybacks by companies, notably in the United States, making those companies vulnerable as well. They are vulnerable to a drop in cash flows linked to a slowdown in growth as well as to an increase in interest rates. This, in turn, leads to a significantly greater risk of insolvency in the future.

The combination of the two points above creates a situation of strong global financial vulnerability. In addition, the situation results in an increase in the number of zombie companies, i.e., companies that continue to operate although they are not structurally profitable. They would go bankrupt with normal interest rates, that is, equal to the nominal growth rate. This makes the overall economy less effective and weakens productivity gains.

Maintaining interest rates too low for too long, when they are no longer required to fight insufficient economic growth and credit, therefore creates a very risky macroeconomic situation in the long term. An asymmetrical reaction in monetary policy can lead to serious financial crises.

This was the situation pre-COVID-19. The financial situation thus became catastrophic at the very beginning of the COVID crisis because the pandemic produced a dizzying drop in production and violent contractions in income and cash flows for companies in several sectors. By the end of March, the financial crisis caused by COVID was already more severe than that of 2008-2009, with stock-market volatility twice as high, spreads shooting up violently, and sudden very problematic liquidity shortages, particularly for investment funds. Fortunately, the central banks responded extremely quickly: they lowered their rates when it was still possible to do so, notably in the United States. They also began to buy public and private debt, including high-yield debt, and sometimes even equities, considerably expanding their quantitative easing policy. They also productively adapted the macroprudential adjustment measures. Central banks quite rightly made it possible to relieve a catastrophic financial situation within a few weeks and supported the efforts of governments in favour of the economy through the massive use of unconventional monetary policy.

If the pandemic doesn’t start up again, the question will arise as to how we can exit this monetary policy when growth returns consistently to a satisfactory level, given that government and company debt has increased much more than before the pandemic? Without abruptly ending the extraordinary support measures implemented by governments and central banks, we will have to start thinking now about the eventual exit from an exceptional situation in which central banks were right to temporarily suspend market logic by putting the monetary constraints for private and government borrowers on hold.

We will be faced with high levels of government and company debt as well as capital-asset bubbles. If we raise rates too quickly via a poorly-planned withdrawal from Quantitative Easing, it could have a disastrous effect on solvency in the private and public sectors. This could lead to a crash in capital-asset markets, which would increase overall insolvency. The exit must, therefore, be very gradual and controlled.

Note that, if inflation wasn’t merely a transitory phenomenon (it is currently increasing because the restrictions weighing down on economies have been lifted and the labour shortage experienced in many high and low added-value sectors is dissipating day by day) this would raise very complex issues for central banks. Should they maintain the solvency of economic agents at the cost of potentially uncontrollable inflation? Or do the opposite?

But, even if a new inflationary period doesn’t arise, should central banks continue their quantitative easing policy ad infinitum if governments and companies do not nolens volens pay down their debt? This would result in structurally higher financial instability, both in terms of over-indebtedness and increasingly extreme bubbles, with the very serious economic, financial and social instability inherent to the inevitable resulting crises. There would be an increasing moral hazard since borrowers, both private and public, would no longer fear over-indebtedness. In addition, investors would understand that they have a free hand thanks to the central banks, which will always protect them from crashes, with no repercussions, and would thus be encouraged to underweight the price of risk in their financial calculations over the long-term. Lastly, the economy would see more and more zombie companies and less of the creative destruction necessary for growth. This would lead to a lasting decline in productivity gains that would, among other things, structurally slow down gains in real purchasing power.

Ultimately, the risk of the unlimited monetisation of debt would also lead to a catastrophic capital flight. A healthy and effective monetary system is, in fact, a reliable and trustworthy debt settlement system. Therefore, if artificial solvency was achieved due to the long-term use of overly-low interest rates, the debt level could continue to rise without any apparent constraints until it created a real crisis of confidence in the value of debt and, eventually, of the currency.

To maintain their credibility and, therefore, their effectiveness, during future systemic crises, central banks must protect themselves against the known risk of fiscal dominance as well as against financial market dominance. In other words, they cannot be dominated by governments, which might demand continuous intervention by the banks to ‘guarantee’ their solvency. However, they shouldn’t be dominated by the financial markets either. Central banks need to be in a strategic relationship with the financial markets. However, they can’t be afraid of channelling them insofar as possible toward areas of sustainable fluctuation, or to counter collective perceptions and opinions when groupthink results in speculative bubbles. They must do so even though markets today are consistently asking for more monetary injections to continue their upward momentum. Jerome Powell, the chairman of the American Federal Reserve said recently, and quite rightly that: “The danger is that we get pulled into an area where we don’t want to be, long-term. What I worry about is that some may want us to use those powers more frequently, rather than just in serious emergencies like this one clearly is”.

However, alongside the policies of the central banks – which need to start thinking now about the best way to eventually escape their ultra-accommodative policies – we need fiscal policies that are sustainable in the medium-term, while taking care not to cause a recession by acting too quickly. It must also be made clear that there will be no ‘magic money’ and that the measures taken during the pandemic were extraordinary and cannot, under any circumstances, be continued over the long term. Governments must therefore implement structural policies (investments and reforms) which are indispensable to increase the growth potential of their economies. They must immediately start to explain that it is time to mobilise to facilitate growth through more work. In France, notably, via pension and labour market reforms, given that many French companies are facing bottlenecks, including in hiring. Ultimately, this is the best way to gradually escape over-indebtedness.

Central banks cannot do everything on their own. Expecting too much of them can be dangerous for the economy as well as for their own effectiveness, when they are called upon again.

Olivier Klein : The crucial role of commercial banks – Banque & Stratégie april 2001

https://www.oklein.fr/en/the-crucial-role-of-commercial-banks/

Olivier Klein : The post-Covid economic paths are very narrow – Les Echos February 16, 2021

https://www.oklein.fr/en/the-post-covid-economic-paths-are-very-narrow/

Olivier Klein : Not repaying debt: risk of a loss of trust in money and risks for society – complete version – Les Echos November 2020

https://www.oklein.fr/en/not-repaying-our-debt-risk-of-a-loss-of-trust-in-money-and-risks-for-society-complete-version/

Olivier Klein : Post-lockdown: neither austerity nor voodoo economics – Les Echos May 2020

https://www.oklein.fr/en/post-lockdown-neither-austerity-nor-voodoo-economics/

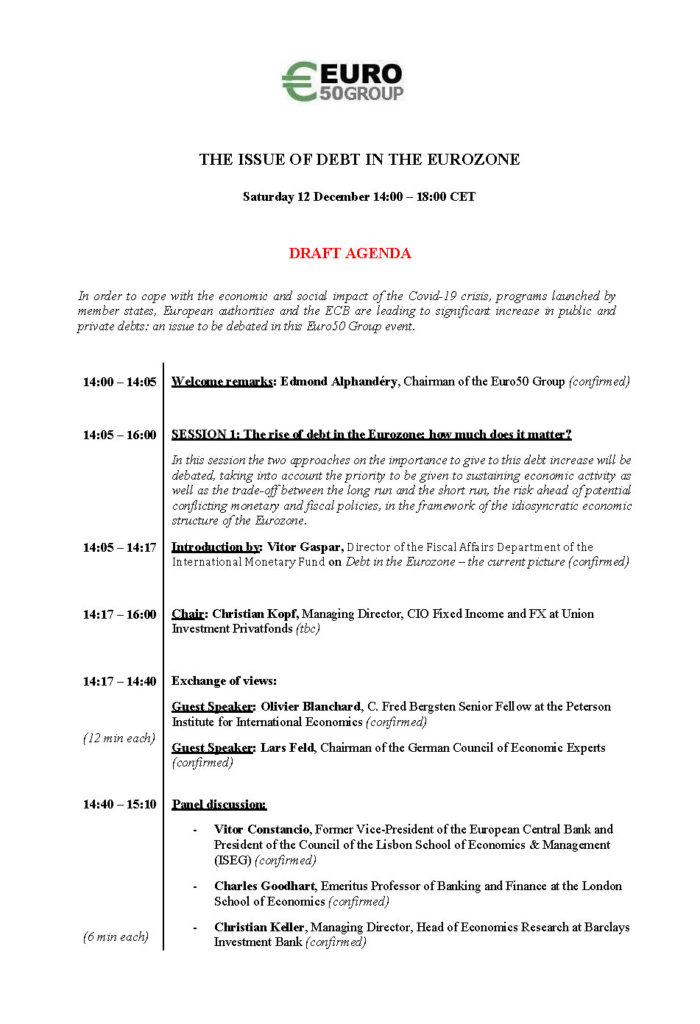

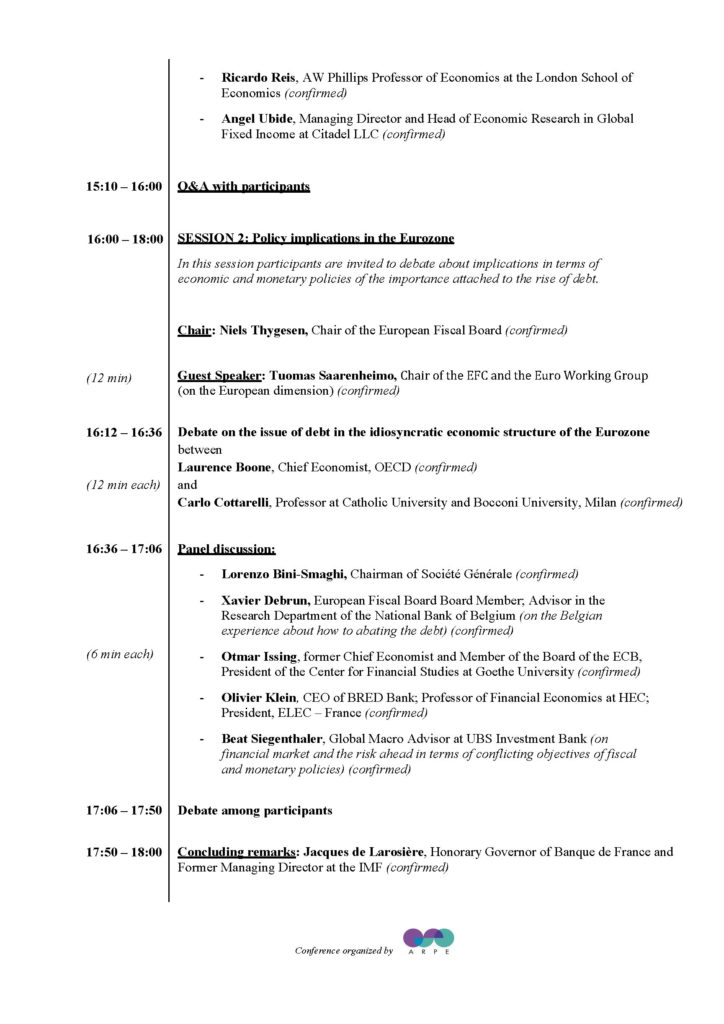

Olivier Klein : The debt issue : risk of financial instability and of a loss of trust in money – Conference EuroGroup 50, 12 décembre 2020

https://www.oklein.fr/en/the-debt-issue-risk-of-financial-instability-and-of-a-lost-of-trust-in-money/