Published by Les Échos on April 7, modified and completed on April 10

Trump has a few central economic ideas that seem to guide his words and actions. And while he appears to many to be disorderly, incoherent, and contradictory, his worries are not devoid of both a sense of reality and coherence. But he seems to have only one weapon to achieve his goals, wielded in a brutal and crude manner: tariffs. Doubtless, along with a weakening of the dollar. But the wielding of these weapons is contradictory and dangerous.

The difficulties of the American economy are not due to its growth rate or productivity gains, which have been significantly higher than those of the Eurozone, particularly for the past fifteen years. On the other hand, between 2000 and 2024, the share of industry in GDP fell from 23% to 17%, with the resulting adverse effects on American workers and middle class.

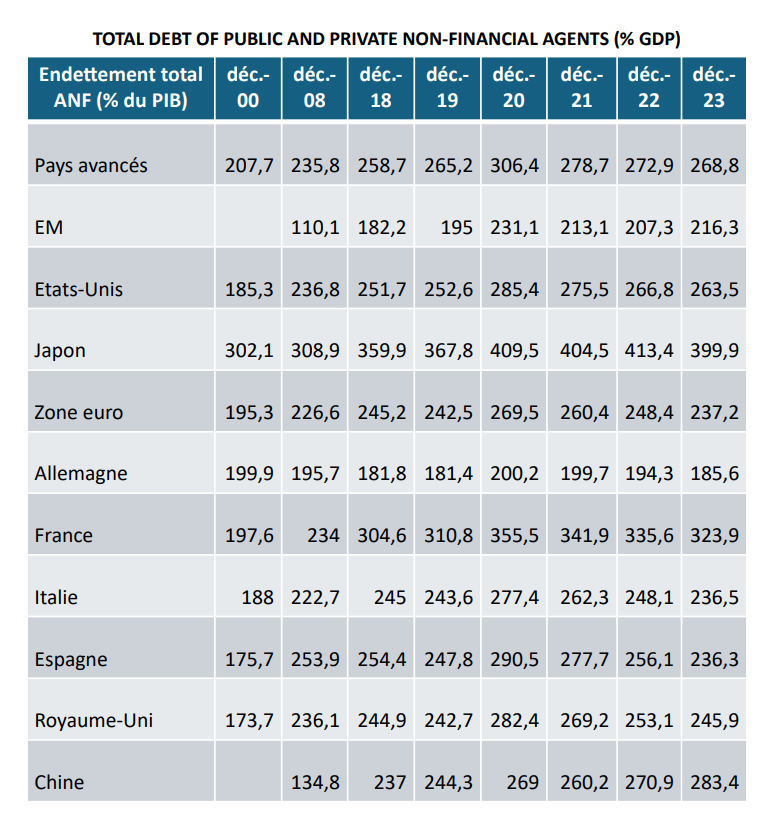

Furthermore, the twin deficits, public and current, have led, over the last twenty-five years, the United States to see its public debt soar from 54% to 122% of GDP and its net external debt multiplied by a factor of 4 (approximately from 20% to 80% of GDP).

Monetary Dilemma

This explosion of both debts will sooner or later pose a problem regarding the dollar’s status as an international currency. However, the United States has a structural need to finance its debts, and therefore a need to attract capital from the rest of the world.

And owning the international currency (approximately 90% of foreign exchange transactions, 45% of international transaction payments, 60% of official central bank reserves) greatly facilitates this financing, since countries with a current account surplus, most often in dollars, almost systematically reinvest this liquidity in the American financial market. Especially since the United States has outperforming equity returns, and by far the deepest capital market.

This status as an international currency also requires the country with this considerable advantage to accumulate a current account deficit over the years so that the rest of the world can hold the amount of international currency it needs, quasi automatically financing this deficit.

But, as in all things, balance is essential, and in this matter, it is difficult to maintain. The United States does not regulate the size of its deficits and debts according to the needs of the rest of the world, but according to its own needs. This, moreover, gives the international monetary system an intrinsically unstable character, as the global currency is merely the debt of one of the system’s players imposed on the others, and not that of an ad hoc institution, not being one of the players themselves.

Robert Triffin, as early as the 1960s, stated that if the United States did not run a sufficient current account deficit, the system would perish from asphyxia. And if this deficit (and therefore the external debt) became too large, the system would die from a lack of confidence.

Faced with the dangerous dynamics of external debt in particular, today Trump must therefore protect confidence in the dollar to perpetuate its financing by the rest of the world without (too much) pain, that is to say at non-prohibitive rates, and, at the same time, try to reduce excess imports compared to exports so that the trajectory of this debt can be sustainable. With a coherent objective of reindustrialisation, thus making it possible to reduce this gap, by limiting imports of industrial products, while making his voters happy.

So Trump is right to be concerned about the unsustainable trajectory of U.S. external debt. The dollar’s role as an international currency goes hand in hand with current account deficits for the country issuing such a currency. However, if these deficits become too large and external debt grows excessively relative to GDP, U.S. creditors might lose confidence in the dollar, potentially causing its value to drop significantly and/or increasing refinancing rates due to higher risk premiums demanded by the global market. This concern is justified.

Fragile Confidence in the Dollar

Yet, Trump seems to have only one weapon in his arsenal to achieve this: tariffs. And the apparent aim of weakening the dollar. At first glance, indeed, both an increase in tariffs and a weakening of the dollar can simultaneously lead to a decline in US imports, an increase in domestic production and in exports, and a need for non-Americans to develop their industries within the United States to maintain their commercial presence.

However, this strategy, while seemingly coherent, clashes with the contradictory need for a stable dollar if we wish to maintain the confidence of the rest of the world, which buys US debt.

Furthermore, the weaponisation of the dollar by previous administrations to enforce financial sanctions imposed by the United States, has already seriously damaged the confidence and desire of the rest of the world to hold unlimited amounts of dollars. Those of the “Global South” countries in particular, which are simultaneously challenging the American double standard.

In addition, the abrupt and seemingly erratic announcements regarding huge tariffs increases are also not fostering confidence in the American economic and financial system, to say the least. This is without even considering their very dangerously regressive potential for the global economy.

Let us also incidentally note that Biden’s IRA had effects similar to tariffs – though much less abruptly and violently- by heavily subsidizing industries producing exclusively in the U.S., which violates WTO rules.

Additionally, the Trump’s idea that the imbalance between U.S. imports and exports is primarily due to unfavorable and unfair conditions imposed by surplus countries is incorrect. While China has built its growth on exports while restricting access to its market, the significant U.S. current account deficit mainly stems from an insufficient domestic competitiveness and from a strong lack of savings compared to investment, that is to say from demand being much greater than domestic supply, leading to huge current deficits and consequently to a evergrowing reliance on external financing.

Instead, structural measures to enhance U.S. industrial competitiveness and public deficit reduction are essential.

In summary, while concerns about maintaining a sustainable trajectory for U.S. external debt are justified, balancing individual current accounts with each country based on perceived abuses by surplus nations is totally misguiding. Furthermore, aggressive use of tariffs or dollar manipulation reflects a crude and dangerous approach to economic policy that is risky, even as a negotiation tool. And lacks theoretical as well as empirical legitimacy.

Protecting Financial Stability

Trump is therefore right about his “obsessions,” but undoubtedly wrong in the nature of his response.

He also brandishes threats against countries that are considering creating alternative payment systems to the dollar, and perhaps soon against those that channel less of their excess savings into American financial markets.

And perhaps he also dreams of transforming their debt obligations to the United States into very long-term, low-interest debt (see Stephen Miran, Chairman of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers). This would, of course, definitely precipitate the rest of the world’s loss of confidence in the dollar.

It is also possible, with the same objective, that he is considering facilitating the development of stablecoins, cryptocurrencies backed by the dollar, in the hope that they will spread worldwide, thus de facto dollarizing the planet. To the detriment of the monetary sovereignty of other regions of the world. We can therefore bet that, in countries around the world, authorities would prevent this by regulating payments within their borders, thus protecting their sovereignty and global monetary and financial stability.

The economic and financial challenges facing the United States are significant. But the solutions to address them are certainly more diverse and more structural than simply imposing tarifs. And, much worse still, very high tariffs, with inevitable retaliatory measures, would lead to a huge global recession combined with a major financial crash.

Olivier Klein is a professor of economics at HEC