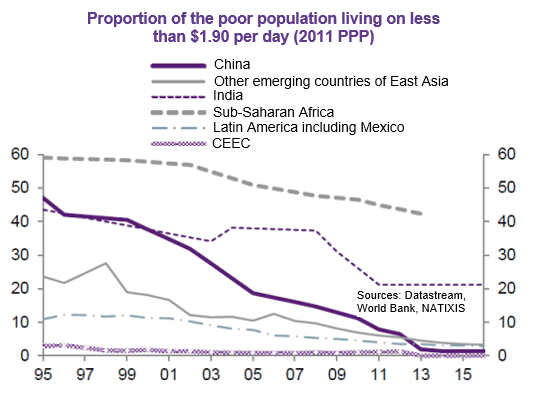

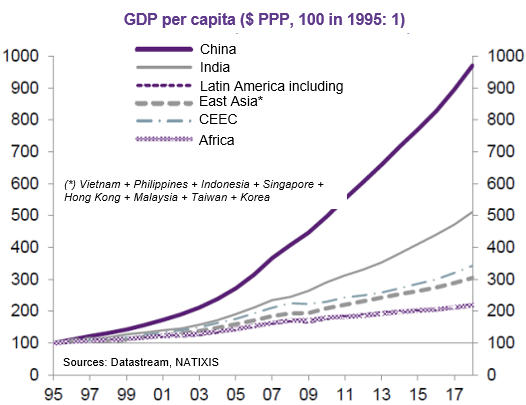

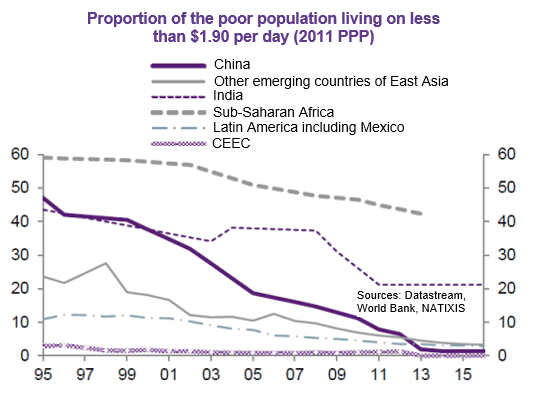

By nature, the topic of inequality covers several aspects. If we look at the global level, levels of inequality between poor and rich countries have decreased considerably since the 1980s. According to the World Bank, 40% of the world’s population in 1981 lived below the extreme poverty line compared with only 11% today. The growth rate of emerging countries has therefore substantially reduced inequalities between the average living standards of the various countries. And if we focus on just China and India, which have experienced and continue to see the strongest economic development since the 1980s, 2 billion people have risen above the poverty line. That’s great progress and one of the obvious benefits of globalisation.

That’s true not only for income, but also for health. My data are less recent, and it has improved even more since then. In 1940, life expectancy in developing countries was 44.5 years. In the 80s, it reached 64.3 years. That’s an increase of 20 years over this 40-year period. Meanwhile, people in developed countries are living nine years longer. Here again, we can see that inequalities in health and life expectancy have decreased.

On the other hand, inequalities within each country, whether developed or emerging, have increased on average with globalisation and growth. That’s because although the growth process allows the greatest number of people to increase their standard of living, some in each country are progressing faster than others, and in some countries, people at the top of the pyramid have access to a larger share of national income. The standard of living has therefore increased for nearly everyone. However, inequality has still managed to grow, simply because certain people’s situations have improved more quickly than others. That’s the nature of happiness, measured by economists in an informative way. All the studies show that happiness is relative. We’re happy when we’re doing better and when our situation improves faster than others. In other words, by comparison. In relative terms. So, even though everyone’s standard of living is rising, the increase in inequality is quickly becoming a social and political topic. We’re therefore seeing a phenomenon needing better clarity: dramatically smaller inequality between countries and growing inequality within countries, even though the level of wealth and well-being has increased overall.

The issue of inequality can therefore be addressed and analysed in various ways.

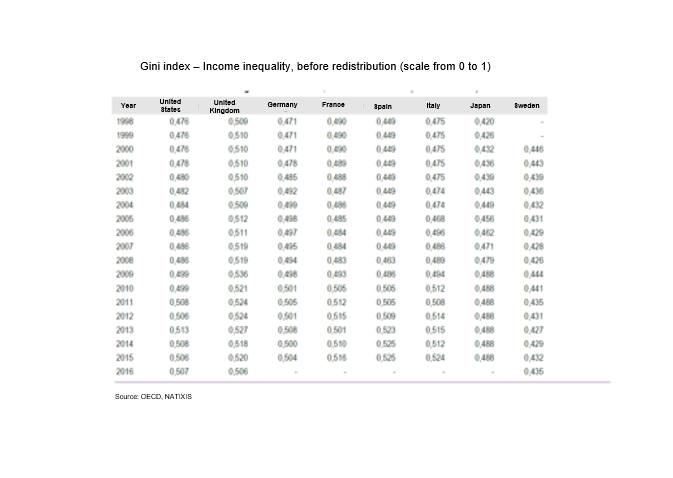

Income inequality can be measured by looking at the share of the country’s income held by the top 1%. Inequality can also be measured much more precisely and undoubtedly with more relevance with the Gini index. Gini was an economist and statistician who invented the method of studying the distribution of inequality across the entire population. We look at the differences between everyone two by two and average the differences from each to each. If the average of the differences is zero, that means that everyone has exactly the same income. An average of 1 means total inequality. These indices are measured across all OECD countries.

Lastly, a third way doesn’t look at income inequality but at inequality of opportunity. Of course, we’re talking about social mobility and the “poverty traps” that generations can fall into. Equal opportunity is obviously crucial because it relates to the republican pact, the social pact, and the ability to live together and obviously because it is fundamental for the health of a society and its cohesion. When inequality of opportunity is low, more people can be mobilised. That means that no matter where you’re born, if you have talent and equal opportunities, you’ll manage to advance. So, not only is the belief that everyone has the same opportunities an important factor of social cohesion, but it also helps to foster growth because it mobilises all talents wherever they are. The issue of inequality of opportunities is therefore crucial. It means knowing whether they are still the same and their children who all have their opportunities to succeed or if the pathways can be fluid without too much determination for the original social environment. And we’ll see that in France, there is a strong adhesion at both the top and the bottom.

Findings:

I’ll start by presenting a few figures and then some analysis.

In France, compared with neighbouring countries, income inequality after distribution is rather low, whereas income inequality before distribution is rather high. Meanwhile, inequality of opportunities is rather high.

We’ll use these findings to try to come up with some possible conclusions in terms of economic policy and necessary reforms.

First, let’s take a look at the measurement of income inequality before distribution and after distribution. Before allocation, it’s clear, for example, that inequality is greater if wages range from 1 to 1,000 rather than 1 to 100. But we also have to consider people who aren’t working and therefore have very low incomes. The more people there are excluded from employment, the greater income inequality before redistribution is.

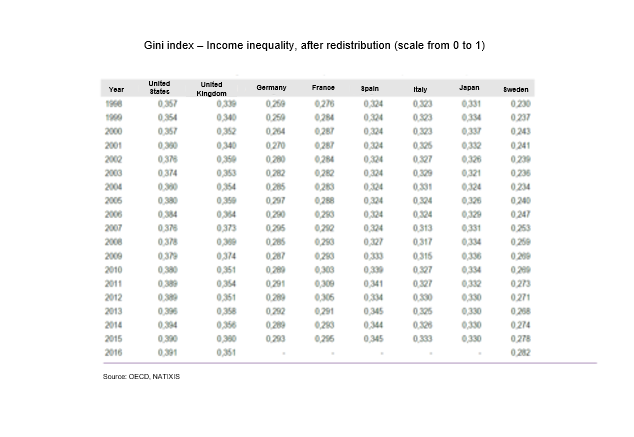

And the more powerful the redistribution system is, whether through taxes, support income, and or other ways, the lower income inequality after distribution is.

Before distribution, the GINI index rose from 0.477 in the United States in 1996 to 0.507 in 2016. In the UK, contrary to what one might think, there has been little increase. It increased from 0.473 to 0.504 in the EU and from 0.409 to 0.488 in Japan. So, what do we see? Inequality has actually risen everywhere. And in the US, it hasn’t risen much more than elsewhere, before distribution. Its level of inequality isn’t really much higher than in the eurozone, while in Japan it’s lower.

After distribution, the US fell from 0.507 to 0.391 in 2016. We can therefore see the effect of distribution. It clearly reduces income inequality. There has been a sharp decline in the UK as well. After distribution, the eurozone is a much more egalitarian system than the US since it’s much lower after distribution there. Europe therefore has a system that does more to reduce inequality. And Japan lies between them.

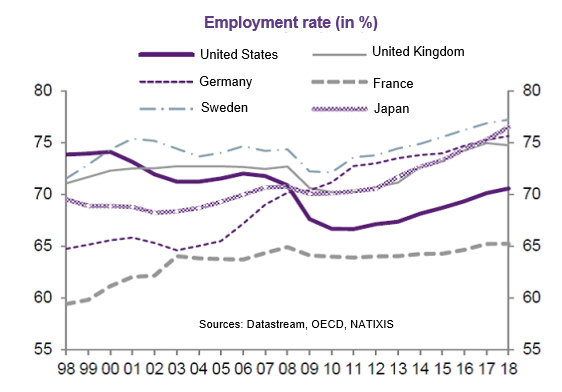

Let’s analyse France. Before redistribution, the Gini index rose from 0.490 in 1998 to 0.516 in 2015. That’s a fairly small upward trend in inequality. Are these inequalities big or small compared with other countries? In 2015, France was a little more unequal before redistribution than the US. Is it because there’s a broader range of wages? Of course not. It’s because there are many more people out of work. That’s an essentially French problem. Other countries very often have an employment rate 10 points higher (75% compared with 65% in France). Germany is almost at the US level. And we know that the unemployment level is very high there. Spain’s level of inequality before redistribution is even greater than France’s. Not surprisingly, Sweden is a more egalitarian country even before distribution. We can therefore see that France had high levels of inequality before redistribution.

But after redistribution, what’s the finding?

In 2015, France was at 0.295, one the lowest indices of all the countries considered. That means it went from having one of the highest indices in terms of inequality before redistribution to one of the lowest after redistribution. We can therefore see that redistribution is very strong in France. In the US, the level of inequality after redistribution is much higher than in France. But in Spain, Italy, and Germany, the level of income inequality after redistribution is about the same as in France. And France’s levels, again after redistribution, are quite comparable to Sweden’s.

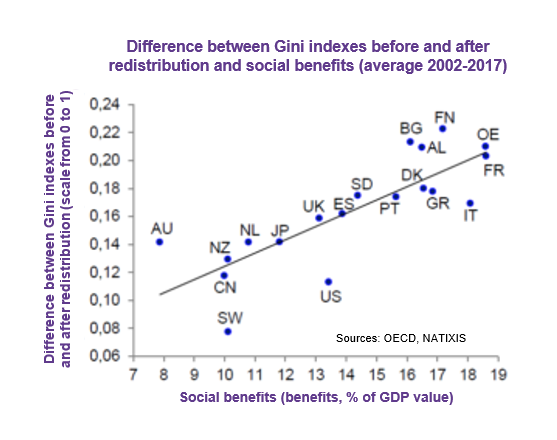

France thus has a one of the highest redistribution policies, relative to GDP, of all OECD countries. The advantage is reduced inequalities, but there are also disadvantages. It means much higher taxes and mandatory contributions, which is not without consequences. We can easily see a correlation between the Gini index after redistribution and the burden of social benefits relative to GDP. And, thanks to one of the strongest redistributions among OECD countries, France has one of the lowest income inequalities. Only Denmark, Finland, and Sweden have lower levels.

Now let’s consider the proportion of national income received by the 1% of individuals with the highest national income. In France, they received 9% of national income in 1995. In 2015, they received 10.5%. For the sake of comparison, Sweden had the lowest percentage at 6% of national income versus 9% in France in 1995 and 8% versus 10.5% in 2015. That’s not a huge difference. Let’s look at the United States. In 1995, the richest 1% received 15% of national income. In 2015, this figure was a little over 20%. That’s clearly a striking figure. It’s twice as much as in France. And the increase in the share received by the richest 1% has been much more brutal. In Germany, growth has been a little stronger than in France. While it was also 9% in 1995 like in France, it was 13% in 2015. However, we’re very far from the US. All in all, the richest 1% have received a growing portion of national income. But the phenomenon is much more visible in the US than in Europe.

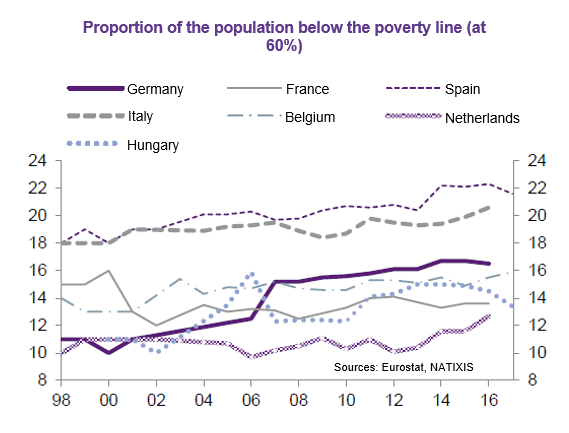

Another way to analyse inequality is to look at the percentage of individuals at the poverty line.

The customary international way of calculating it can be called into question, but at least it’s an indicator used everywhere. We look at the median income of the French or Americans, for example, as a percentage. Anyone under 50%, or 60% like in our figures on this medium income, is considered poor. It is a relative notion of poverty.

In France, few people are below the poverty line, meaning below 60% of French median income. Meanwhile the percentage is higher in Spain and Italy. It’s also higher in the US. And the percentage of the French population under the poverty line even decreased between 1998 and 2016. It increased in Germany over the same period.

So, again, we can’t say that poverty is high or has increased in France. What we sometimes hear in the media is simply statistically false.

However, in France, inequality of opportunity is rather high compared with similar countries.

According to opinion polls conducted by the OECD, 44% of French respondents believe that education passed down by parents is important for progress through life. In the OECD, which includes Chile, Mexico, all European countries, the United States, etc., the average opinion is at 37%. This reflects a rather high sense of inequality of opportunity in France. Unfortunately, this opinion is correct. In France, socio-economic status is passed on more strongly than elsewhere from one generation to the next. The relative income level is passed on more strongly from one generation to another than in other countries. Lastly, the level of education and diploma is passed on more strongly from parents to children than in other countries. According to these three criteria, inequality of opportunity is greater in France than elsewhere.

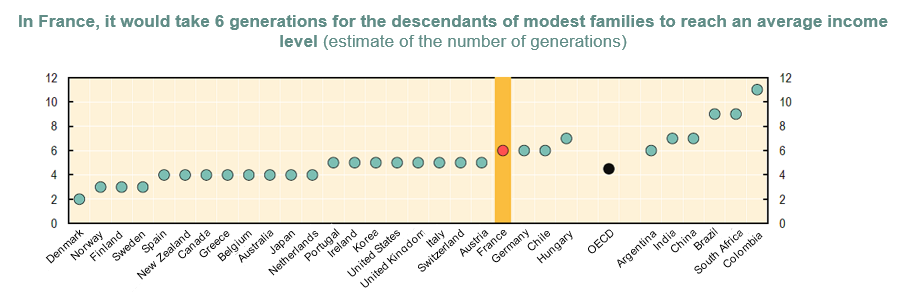

Of course, inequality of opportunity exists everywhere, since the socio-cultural environment is very important in the life and development of children. But the way we manage to partially correct the phenomenon can be more or less strong. The OECD calculated this and published a report on this subject, taking intergenerational mobility into account. Then we look at how many generations it takes for a family at the bottom of the ladder to reach the middle range. Clearly, the fewer generations required to reach the average, applying the average mobility of society, the less inequality of opportunity there is. The more generations it takes to achieve this, the more one is confined to the bottom of the ladder or symmetrically protected at the top of the ladder.

In Denmark, it takes 2 generations.

In Norway, 3; in Finland, 3; in Sweden, 3; in Spain, 4.

In New Zealand, Canada, Greece, Belgium, Australia, Japan, and the Netherlands, 4.

In the United States, 5.And in France, 6.

Six generations so that someone at the very bottom of the income ladder has a chance that their great grandchildren will reach the middle income level, given French mobility. Germany doesn’t do better, and neither does Chile! And the average for the OECD is between 4 and 5.

Studies have reached the same conclusions about the inequality of opportunity in France, relative to comparable countries, by calculating the correlations between the income of parents and the income of children once they reach adulthood. The findings regarding correlations of diploma level are similar.

What structural reforms should be done to combat inequality of opportunity?

Of course, the reform of national education must be mentioned. There is currently much less mobility and equality of opportunity in France than many years ago when teachers who supported and pushed their deserving pupils were called “horsemen of the Republic”. This state of mind has not been abandoned, but it is much less widespread, and in reality, national education has declined in overall effectiveness for many reasons that can be explained more or less easily. The effectiveness of education is measured and compared using level tests carried out internationally by the OECD.

Comparative studies show that national education must be able to devote slightly more resources to children in disadvantaged areas or neighbourhoods. It’s also known that a lot comes into place early in life, in kindergarten, and in elementary school. That’s where more resources are needed. But let’s not fool ourselves. It’s a question of efficiency and not global means within national education in France, which has a much higher budget-to-GDP ratio than the other European countries for a disappointing result in the tests.

People also must be supported during their career so that they can progress. Professional training in France is very inefficient and is in the process of being reformed.

Some countries do all this remarkably well, such as South Korea and the Nordic countries. They equip themselves with the means to ensure a good degree of social mobility in their country. Once again, that’s useful, not only for social cohesion, but also for the economy because there will be a search for talent that otherwise wouldn’t be able to express themselves and obviously contribute to the general growth.

In addition, long-term unemployment needs to be reduced, which means more effective support for returning to work and better incentives to take up a job. We also know very well that people in France are entitled to unemployment after four months of work. It’s one of the few countries where it takes so little time to be entitled to unemployment. That should be looked at. And, of course, we contributes to the creation of jobs must be facilitated…

It’s also important to work on territorial inequalities, because they exist.

So, there’s generally less social mobility in France than in other comparable countries, and this is reflected in the evolution between generations through income, degrees, and socio-professional categories.

Plus, we know that low mobility is not only intergenerational, but there is also fewer chances in France than elsewhere for people to be able to evolve during their life.

Two analyses:

From all this, I feel that there are two analyses that need to be given thought.

The first is the link between growth, innovation, and equal opportunities. The second is strong redistribution, which greatly reduces the initial inequalities that lead to a vicious circle.

First angle of analysis is the link between growth, equality, and innovation. For 20 years now, we’ve been living in a context of globalisation and a technological revolution related to digital. These two phenomena are increasingly eliminating repetitive work and the corresponding jobs.

Today, growing in an economy that is no longer a catch-up economy like in the post-war year requires being innovative. Innovation is crucial as the current driving force behind the growth of countries at the “technological frontier” (1). Emerging countries are catching up to developed countries, which must innovate constantly to continue to grow as emerging countries grow very quickly.

That means that we’re in an economy of knowledge and innovation – the only way to create growth and wealth.

As a result, we have to make sure to encourage innovation in our economy and our institutions (for example, organisational methods, labour market, and legislative framework). There’s also a link with equal opportunities because it’s obviously easier to fight poverty when there is growth. And it’s also easier to ensure social promotion to provide social mobility. If we step back and look at ourselves as a company rather than a country, we know that in a company that doesn’t develop, it’s very difficult to develop employees and help them grow. In a growing business, all those who are motivated and talented can be helped to grow.

Growth is therefore needed to reduce the inequality of opportunity and permit social promotion and mobility. If we don’t have enough growth and innovation, we end up with a blocked or jammed society and insufficient social mobility, and this leads to many social cohesion problems. In addition, as I already mentioned, the more we manage to promote equal opportunities, the greater the number of mobilised talents will be, and their energy will contribute to growth. So, we see the virtuous link between these different factors.

Plus, innovations create breakthroughs, which then create new sources of growth and wealth. Innovation therefore calls into question accrued benefits. And that’s also what enables social mobility. In the US, if we suddenly see people appear in the wealth rankings and develop new businesses very quickly, it’s because they seize innovations and can experience some amazing personal developments.

I’m not saying that this is a model in itself, but simply that, even at smaller scales, it’s essential. The more innovation, capacity to invest, and growth there are, the more it is possible to go beyond pensions and promote social mobility.

We therefore have to know how to ensure policies that facilitate innovation and promote this phenomenon. Once again, the innovation economy is the economy of knowledge: it’s education, it’s professional training, and it’s the promotion of all talents. It’s also means eliminating “poverty traps” by, as I already mentioned, better incentives to work, better support in finding a job, and easier abilities to switch jobs in shifting economies.

And that too is part of the necessary structural reforms. To encourage technical progress and innovation, competitiveness must also be encouraged through investment.

The second area of thought is the analysis of income inequalities before distribution and after distribution and the cost of this distribution (2).

The rather high income inequality before distribution is offset in France by redistribution, which is a strong redistribution because inequalities aren’t liked in France. In a way, what’s honourable is a collective choice. But a strong redistribution has a high cost in terms of social benefits and naturally social contributions and taxes. And because this leads to a lot of levies on companies, it spills over onto competitiveness. And lower competitiveness translates into fewer jobs. And the loop goes on. Because if there are fewer jobs, there are much stronger pockets of poverty and therefore large income inequalities before distribution. And then there’s long-term unemployment that must be offset by more redistribution and therefore more business costs. This leads us into a vicious circle.

The goal should therefore probably be to avoid over-repairing. Repairing is certainly normal, but better still is to do better upstream, to reduce income inequality before redistribution and avoid falling into this vicious circle. Prevent rather than repairing a lot of things.

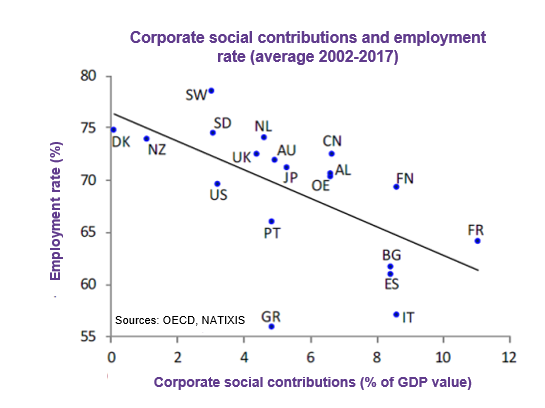

The employment rate in France is 65%. That’s around 10% lower than in comparable countries. This is an unacceptable situation in itself. In France, there aren’t enough working-age people who are working. If we consider the two extremes, between the ages of 60 and 65, there are far fewer people working in France than elsewhere. Much fewer than in Germany, not to mention Sweden, in comparing France to countries with comparable models. Similarly, it’s very difficult for young people to find a job. And we can see the correlation: the lower the employment rate is, the higher the social benefits needed to offset the created inequalities.

Now let’s consider the correlation between employment rates and the size of distribution policies. In other words, employment rates and differences between the GINI indices before and after distribution. France has the strongest redistribution policies and the lowest employment rates.

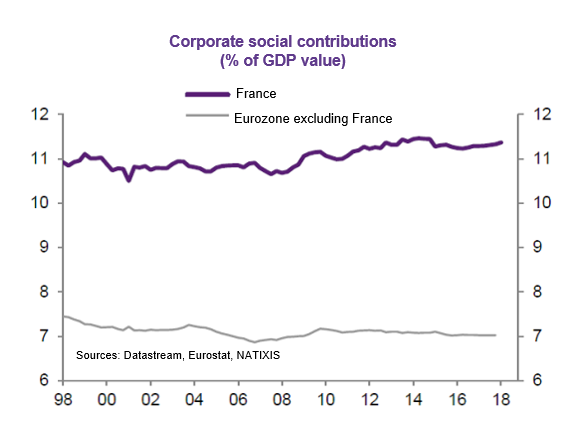

Again, the correlation is obvious for OECD countries. Because of France’s significant redistribution policy, its social security contributions are roughly 60% higher than the eurozone average and therefore the contributions of neighbouring and comparable countries.

Companies are therefore structurally less competitive. After social contributions, there are left with a considerable disadvantage in terms of the overall cost of labour. This then means a lack of jobs, resulting in large income inequalities before redistribution. Hence the fact that we redistribute strongly… I don’t think redistribution should be stopped. That’s not my point at all. But to do sound, normal redistribution that doesn’t cost in terms of growth and jobs, we must strive to allow many more people to work and therefore allow our businesses to be more competitive. Otherwise, we enter a vicious circle.

Therefore, the challenge is to ensure that, even before redistribution, there are fewer inequalities because many more people are working. Taking action upstream to repair less means entering a virtuous circle, and this obviously means allowing many more people to work, resulting in less income inequality before redistribution and, at the same time, increasing equality opportunities. More working people means more self-sufficient people, far fewer pockets of poverty, and many more socialised people, because work is one of the main forms of socialisation.

Let’s hope that these figures and findings, sometimes unexpected because they are little-known, like these analyses, will be able to contribute to a useful debate about the effective reforms to be conducted, without preconceptions or confusion between the ultimate objective of reducing inequalities, with a primary focus on the high inequality of opportunities in France, and the means to be used to achieve it.

In the words of Bossuet: “God laughs at men who complain of the consequences while cherishing the causes”.

(1) On this topic, see Schumpeterian growth theory by Philippe Aghion.

(2) – The analysis of the cost of redistribution and the vicious circle created between income inequalities before and after redistribution and the lack of competitiveness of French companies was developed by Patrick Artus in several ‘economic flashes’.